The Gothic and Brutalist styles of architecture are very different from each other in terms of how they look. The medieval cathedral is on one side. It has flying buttresses, sculpted stone, and a kaleidoscope of stained glass. On the other hand, there is the stark, monolithic geometry of raw concrete, or béton brut.

But if you look more closely at the Brutalist churches from the middle of the 20th century, especially those built during the religious revival after World War II, you can see a deep, almost genetic connection to their Gothic ancestors. This is not a kinship of looks, but of fundamental structural thinking. Brutalism, at its most spiritual level, is the Gothic ideal without any extra decoration.

The secret is easy to understand: both trends turned down decorative cladding in favor of an honest expression. The Gothic architects used their buildings to show off their style, and the Brutalists did the same, but instead of carved limestone, they used steel-reinforced concrete.

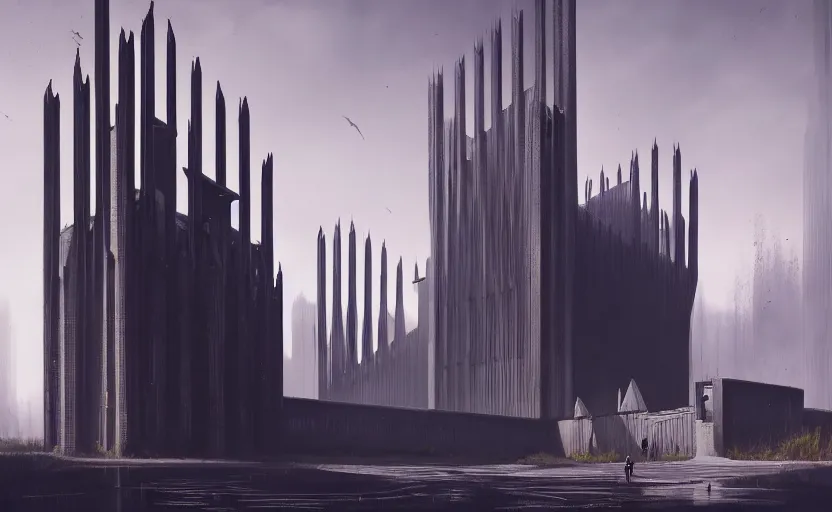

exterior shot of utopian brutalist gothic architecture with cinematic lighting by zaha hadid peter zumthor and renzo piano and, darek zabrocki and greg ruthkowski, simon stalenhag, cinematic, holy place, paradise, scifi, futurism, atmospheric, concept art, artstation, trending on artstation

The Great Structural Divorce: Form Over Decoration

Architectural theory typically sees Brutalism as a response to everything that came before it, especially revival styles that make people feel nostalgic. But when you think about the spiritual architecture of the time, the main premise is very old-fashioned: that a building’s aesthetic truth should come from its materials and how it was built.

Augustus Pugin, a 19th-century theorist and supporter of the Gothic Revival, said that decoration should never hide construction. A hundred years later, the Brutalists did this by refusing to use certain materials. By not finishing the concrete—béton brut—the structure and the surface become one.

The detailed rib vaults and articulated piers of a Gothic cathedral weren’t just for show; they were the important, exposed structure that held up the huge stone ceilings and made room for windows in the walls. When a Brutalist architect like Marcel Breuer built a church, the building did the same expressive work. The only “ornament” of the Brutalist is the rough, board-formed texture of the concrete, which is a direct and honest record of how it was made.

Brutalist interior

The Tyranny of the Vertical: Height and Structural Daring

The most important thing about Gothic architecture is how tall it is. The goal was to get stone closer to the heavens. The flying buttress made this ambitious, even perilous, engineering feat possible. It moved weight out to the sides, which made thin walls and unprecedented height possible.

Brutalist architects in the middle of the 20th century solved the same structural challenge for large buildings, but they exploited the monolithic flexibility of reinforced concrete.

Brutalist Architecture in the Soviet Union

Think about St. John’s Abbey by Marcel Breuer

The church in Collegeville, Minnesota, was finished in 1961. The Benedictine monks who ordered the building wanted it to be a tribute to the pioneering spirit of their medieval ancestors who created the Gothic architecture.

Breuer didn’t build buttresses; instead, he built a huge structure with dramatic folds. The nave’s roof and walls are made of a thin, fireproof drape of reinforced concrete that has been stiffened into huge, rhythmic folds. This folded plate construction serves as both the roof and the side support system at the same time. It is a modern, monolithic version of the Gothic’s exposed structural skeleton. The towering, freestanding bell-banner, a soaring concrete slab with just holes for bells and a cross, stands as a vertical focal point, mimicking the colossal spires of any great medieval church.

St. John’s Abbey Church, designed by Marcel Breuer

The New Stained Glass: Light as a Structural Element

One of the most significant but often ignored connections between the two styles is how much they both love to play with light to make things look divine.

Gothic cathedrals used huge stained-glass windows to turn sunlight into bright, colorful stories that lit up the inside with a heavenly radiance. It was a search for brightness and lightness.

Brutalist churches frequently have darker, more contemplative designs, but they also see light as an important spiritual element. Instead of fully dematerializing the walls, they employ the thickness and bulk of the concrete to control the light with surgical precision.

The best example of this is Gottfried Böhm’s Neviges Pilgrimage Church in Velbert, Germany, which was built in 1968. The church is built on a “cathedral scale” and is a jagged, crystalline monolith made of raw concrete.

Inside, the huge, angled concrete planes are broken up by many small, oddly shaped, brightly colored windows instead of huge sheets of glass. Böhm personally made these windows, which are mostly deep reds, blues, and greens. They look very different from the grey concrete. Because these apertures are so deep, the light is a contrast: a focused lance of bright color cutting through the gloom around it. This generates a dramatic, awe-inspiring, and devotional mood. It has the same mystical impact as Gothic stained glass, but it uses shadow, mass, and focused light instead of glass.

Stained Glass Light as a Structural Element in gothic

Case Studies: Contemporary Monoliths, Medieval Spirits

The building of these two important cathedrals solidified the shift in philosophy from Gothic to Brutalism:

Marcel Breuer and St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota

Breuer’s design showed clearly that a modern religious building might be as big and structurally expressive as a Gothic cathedral without using any old decorations. The huge, cantilevered concrete balcony over the main entrance shows off structural mastery in a big way. The stained glass on the north wall has a honeycomb-like pattern that is similar to the intricate tracery found in a Gothic rose window. This turns a functional surface into a monumental, light-diffusing scrim.

St. John’s Abbey Church / Marcel Breuer

Gottfried Böhm and the Crystalline Neviges Mariendom

People commonly call Böhm’s church a “concrete mountain” or a “tent.” It is a work of art in dynamic, expressive geometry. The pyramidal shapes of the roof and the rough texture of the board-formed concrete walls make you feel like you’re in a huge, old, stone-like cave. The structure is the architecture, which meets the basic, religious need for massive space and structural truth that were the hallmarks of the great Gothic works. The material itself is what makes the inside space feel so dramatic and overwhelming, not the decorations that are put on it.

The jagged, amorphous volume of the church and its cavernous interiors connect with the mountaineous terrain of the regionImage Credit: Steffen Kunkel

A Timeless Truth in Unprocessed Materials

The Neo-Gothic DNA of the Brutalist church shows that the ideals of great building will always be true.

Brutalism did not follow Gothic in style, but in how it was built. By showing off the bare beauty of concrete, these architects brought back the old belief that a building’s strength, height, and skeleton should be its most beautiful features. They took away the carving and the tracery from the flying buttress and the ribbed vault, leaving only the structure and the vertical ambition for a new century.

The austere concrete monoliths of the 20th century are compelling, and often contentious, reminders of a reality that will always be true: when structure is perfect, decoration is not needed. In their own way, they are the most honest and structurally sound heirs of the great Gothic work from the Middle Ages.

Reference:

The Brutalism Renaissance: Power, Raw, Timeless | by Jeune Fléau | Medium

The Distinctive Characteristics of Brutalist Architecture | ArchitectureCourses.org

For more blogs like this CLICK HERE!!