For hundreds of years, mortar has been the quiet partner in building the strongest structures in the world, from Roman aqueducts to modern skyscrapers. But if you ask a regular person what it is for, they’ll probably say it’s the glue that ties bricks or stones together.

People sometimes think of mortar as just an adhesive, but this is a big mistake because it doesn’t take into account its important and complicated technical duties. Professionals in the construction industry don’t see masonry mortar as an extra; they see it as an important, multi-purpose part of the wall system that affects its strength, durability, and performance.

Masonry mortar is a complex structural substance that does four main, interrelated jobs that go beyond just sticking things together. Knowing these responsibilities is what makes the difference between a wall that lasts a long time and one that falls apart too soon.

Masonry Mortar Types and Joints – Archtoolbox

image size:750×500

The Structure’s Foundation: More Than Just Glue

The main job of mortar is to hold together various pieces of masonry, such bricks, stones, or concrete blocks, forming what engineers call a monolithic mass. This cohesiveness turns hundreds of discrete, distinct parts into one big structural piece that can stand up to both vertical and horizontal stresses.

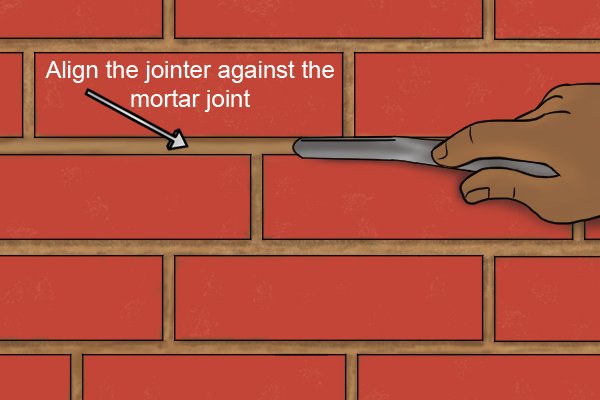

But a mortar joint also has a strange purpose: it keeps the units from touching each other.

The mortar makes the bedding surface even by filling in the gaps and bumps that are sure to happen between units. This makes sure that there is the most contact possible and generates the “extent of bond” needed for the structure to work. The masonry units would only meet at a few high spots without this plastic, conforming covering. This would cause point-load stresses and make the wall less durable. The quality of this first interaction is very important for getting the strongest bond possible. This is because the mortar’s workability and water retentivity affect it.

Align the jointer so it is ready to compress the mortar in-between the bricks.

The Unseen Workhorse of Structure

How to Distribute Loads

The units, such as bricks or blocks, give the wall much of its compressive strength. The main structural role of the mortar is to equally spread the loads that come from above (the roof, upper floors, etc.) across the length and width of each unit below it.

This even distribution is really important. If the mortar was excessively hard or not mixed evenly, it could cause localized stress concentrations that could cause cracking or structural failure. The mortar needs to act as a cushion, moving and spreading the weight so that each brick can support its portion of the load as it was meant to.

A Part that Can Be Sacrificed for Long Life

The comparative strength of the mortar itself is a less well-known but important structural function. According to standard technical rules, mortar should always be less strong than the masonry units it holds together.

Why? If there is too much weight or an unexpected movement, the cracking is purposely directed to the mortar joints. It is easier and more cheaper to repair or repoint mortar than it is to repair or repoint the actual brick, stone, or block unit. This design philosophy makes the mortar joint a sacrificial part of the wall, which means that structural problems will only affect the part of the wall that can be fixed the easiest. This protects the strength and durability of the whole structure. This idea is very important, especially when it comes to preserving history.

From triscosystems.com

From triscosystems.com

The Importance of Protection: Sealing and Longevity

The mortar’s main structural job is to hold things together, but its most important job for longevity is to keep the environment out.

Mortar keeps water, air, and other outside things from getting into the joints. A mortar joint that is well-placed and well-tooled functions as a barrier to keep moisture out, which can cause serious damage over time. The freeze-thaw cycle, in which water gets inside a wall and freezes and expands, can quickly destroy it in cold weather. The mortar protects the whole wall assembly by making the junction watertight. This stops rust from forming in any internal steel reinforcement and reduces efflorescence.

Some mortars, especially those with hydrated lime in them, can also cure themselves. This is called autogenous healing. This amazing feature lets the mortar “self-heal” micro-cracks over time by re-carbonation, which adds another layer of self-repair and strength to the structure.

Two men installing tiles Source: istockphoto.com

Flexibility and Movement: The Unseen Cushion

Structures are never still. They are always moving a little bit because of changes in temperature (thermal expansion and contraction), moisture absorption, and modest settling of the foundation. If the “glue” was too hard, the whole structure would break right away under these forces.

Masonry mortar, especially softer versions like Type N or Type O (and traditional lime mortars), is made to let this small, required movement happen. It gives the masonry units the flexibility they need to move a little bit without breaking the blocks or bricks. This strength is important for keeping the building airtight and structurally sound for the rest of its life.

To put it simply, the mortar acts as an elastic buffer between the hard masonry matrix and the pressures that life and weather put on a building.

Picking Your Structural Partner: Types of Mortar (M, S, N, O)

Because mortar serves so many different and important structural purposes, it is divided into different categories based on its compressive strength and composition (as described by the ASTM C270 Standard Specification for Mortar for Unit Masonry). Choosing the proper kind is an engineering choice, not a question of convenience.

Mortar Type: Type M

Minimum Compressive Strength (psi): 2500+

Typical Structural Use: High-strength, load-bearing walls, foundations, retaining walls, and below-grade applications.

Mortar Type: Type S

Minimum Compressive Strength (psi): 1800+

Typical Structural Use: Below-grade exterior walls, masonry exposed to severe weather, or where moderate lateral loads (wind/seismic) are present.

Mortar Type: Type N

Minimum Compressive Strength (psi): 750+

Typical Structural Use: General purpose, above-grade, exterior load-bearing walls. Offers a good balance of strength and workability.

Mortar Type: Type O

Minimum Compressive Strength (psi): 350+

Typical Structural Use: Non-load-bearing interior walls and historic preservation/repointing delicate masonry.

Type M and Type S are the strongest types and are best for situations where there is a lot of weight or exposure to the elements. Type N is the best all-around type since it has a good combination of bond strength and flexibility. Type O and even softer Type K mortars are only for non-structural work or for working with softer, older masonry units that need a junction that is really sacrificial and flexible.

Source: aamasonry.ca

Conclusion: An Important Part, Not an Afterthought

Masonry mortar serves a structural purpose that goes well beyond that of a simple glue. It is a load distributor, a part that can be sacrificed, a necessary weather seal, and a flexible cushion, all in one properly measured material.

It is very important for builders, engineers, and homeowners to understand how complicated this is. The type of mortar you use has a direct effect on how strong, durable, and long-lasting the whole structure is. The thin joints are what make the brick wall strong. They are the dynamic, engineered backbone of the masonry system. They are not only glue; they are the most important structural partners that make sure that every block and stone lasts.

For more blogs like this CLICK HERE!!

Reference:

Functions of Mortar in Masonry Construction

Understanding the Role of Mortar in Masonry: Types and Uses – Turnbull Masonry