Introduction: A Cathedral Made Possible by Cross-Cultural Genius

The magnificent Gothic cathedrals of Europe, like Notre-Dame in Paris, the soaring spires of Cologne, and the bright heights of Chartres, are huge examples of how smart people were in the Middle Ages. When we gaze up at their huge, open naves and the fine tracery of their stained-glass windows, we can see a whole new way of building things.

But here’s the interesting thing that people often miss: the most crucial new idea that made this huge leap in architecture possible was not a European idea.

The pointed arch is that new idea.

Gothic design is known for its pointed arches, which are a big change from the semi-circular Romanesque arch. This change made it possible for walls to be thinner and buildings to be taller than ever before. The Gothic’s Great Borrow is one of the most popular subjects for architectural blogs in 2025. It shows that even the most famous European style is the result of cultural interchange.

The Romanesque Problem: Why Round Arches Couldn’t Reach the Sky

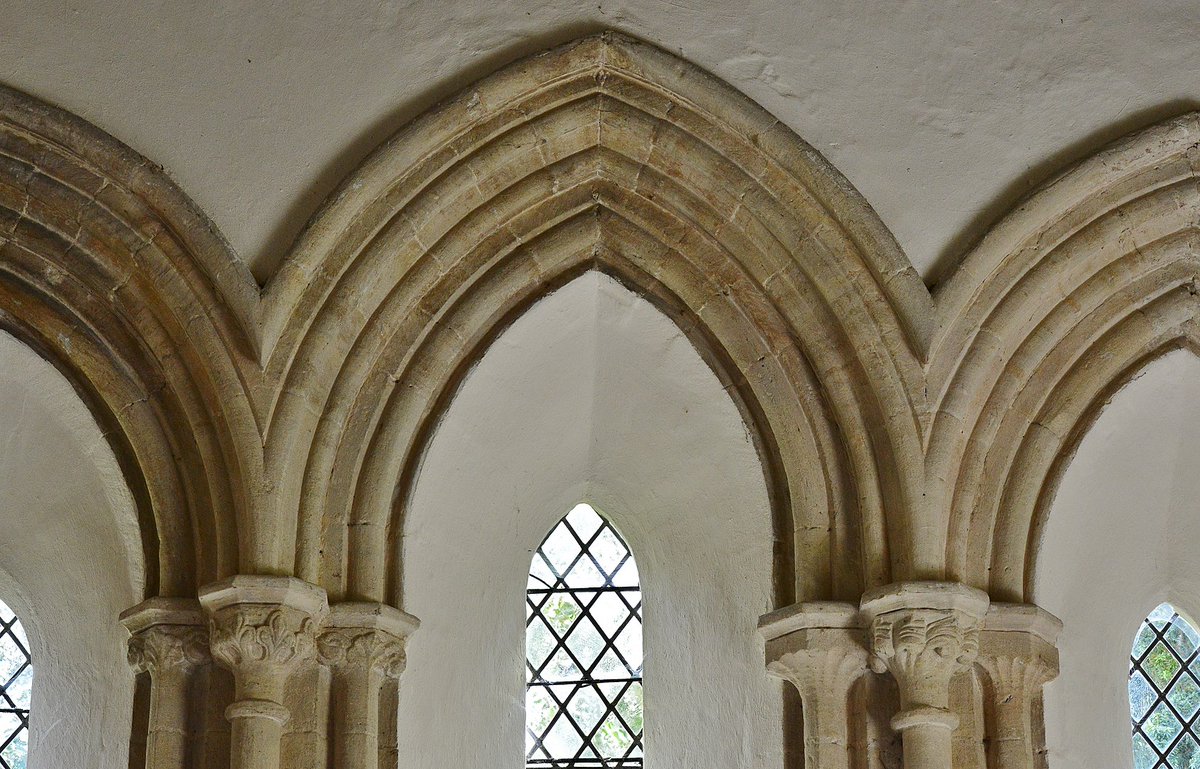

To fully appreciate the brilliance of the pointed arch, we must first recognize the shortcomings of the Romanesque architectural style it supplanted.

Romanesque builders used the semi-circular arch and the huge barrel vault virtually all of the time. The round arch was strong, but its shape let it push outward against the walls that held it up, which is called lateral thrust. Romanesque walls had to be very thick and strong so that the whole building wouldn’t fall out. This meant that the windows had to be narrow and deep-set.

The end effect was a strong, fortress-like building with a dark, hefty inside. Medieval architects wanted their buildings to be tall and bright, like heaven. But the Roman arch was actually holding them down. They wanted a part of the structure that could send weight down instead of out.

Source: rattibha.com

The Pointed Arch: The Silent Revolution

The pointed arch was the best answer.

The pointed, or ogival, arch is stronger by nature than the semi-circular arch. The weight goes down considerably more steeply when the two curves come together at a sharp point. This one small improvement let builders cut the lateral thrust by as much as 50%, which changed the way building works in a big way.

This breakthrough has a huge domino effect:

Thinner Walls: The walls lost most of their weight.

More Windows: Thin walls could be opened up to let in a lot of stained glass.

More Height: The vertical stress was safely handled, which made the high naves that are characteristic of Gothic form possible.

The pointed arch wasn’t only a design option; it was a need for engineering. It was the architectural key that made the Gothic era’s buildings stand up straight.

Source: architecturecourses.org

Following the Route: From Damascus to Europe

The arch is most known in Europe, yet it was used in a methodical and structural way in the Islamic world hundreds of years before the first Gothic church was built. Sir Christopher Wren, an English architect from the 17th century, said that the “Gothic style” should really be named the “Saracen style.”

The path of architectural knowledge migration was complicated and went via many different places:

The Moorish Gateway (Al-Andalus)

Moorish Spain (Al-Andalus) was an important link between Europe and the Middle East in terms of ideas and buildings. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, which was finished in the 10th century, was one of the first buildings to use pointed arches, and it was also one of the first to use horseshoe arches. European explorers, traders, and scholars came across these forms in person.

Moorish Architecture: The Majestic Designs of Al-Andalus / Medieval Castles, Medieval Times

The Middle East and North Africa

In the Middle East, the pointed arch was used for structural purposes even earlier. The Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo (9th century) and the pointed arches employed in Syrian defenses were real examples of the technology long before the foundations of Saint-Denis were erected.

Arch portal of a Masjid in Samarkand,

Uzbekistan

The Crusaders and the Pilgrims

While sometimes exaggerated, the interactions that took place during the Crusades and pilgrimages showed Western builders and knights how much better Middle Eastern religious and military buildings were at holding up. The architectural forms were literally taken back as intellectual cargo.

Crusades

The Gothic Trinity: Vaults, Buttresses, and Bright Space

The pointed arch was not merely copied by the European builders; they used it in a whole new way to build things. For example, Abbot Suger built the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis near Paris in the 12th century.

The pointed arch was the key to the Gothic Trinity’s growth:

Ribbed Vaulting

Ribbed vaulting was possible because of the pointed arch. This complicated, skeleton roof structure has a light frame made of pointed arches (ribs) that cross each other. The roof’s weight is focused on these thin ribs, which thus move the load to certain spots on the wall instead of spreading it out along the whole length of the wall.

Flying Buttresses

The ribbed vaulting focused the outward force on certain spots, so the outside support could be focused in the same way. The flying buttress was made to catch this point load and securely move it down to an outside pier. This freed the main wall from its structural responsibility. The flying buttress could never have been so light and beautiful without the pointed arch.

The Wall of Light

Since the walls were no longer load-bearing, they could be taken down and replaced with huge areas of colored glass and complex stone framework (tracery). Abbot Suger is well-known for wanting to build a “wall of light,” which he saw as a way to show heavenly truth. The tall, bright aspect of Gothic architecture is directly due to the structural efficiency that was established in the East.

Gothic interior featuring pointed arches, ribbed vaults, intricate stone carvings, stained glass windows, polished stone floors, and carved wooden furniture.

Geometric and Decorative Synthesis Beyond the Arch

The pointed arch was the biggest thing they borrowed, but it wasn’t the only one. A closer look shows that the Gothic style itself combined things from all across the Mediterranean:

The Trefoil Arch: This beautiful arch, which looks like a leaf with three lobes, was used in Gothic design to represent the Holy Trinity. It is based on Syrian and Byzantine architecture from the 5th and 8th centuries.

Geometric Complexity: Gothic tracery in windows and stone screens is known for its intricate geometric patterns. These patterns were quite advanced in Moorish and Persian architecture, where a long history of geometry led to complex, interlocking forms.

The Spires and Pinnacles: The image of a multi-story, slender tower that draws the eye higher was reinforced by the prominence of minarets in Islamic cities, which were constructions that also emphasized the verticality of the urban landscape.

Source: pinterest.com/

Conclusion: A Legacy of Collaborative Innovation

People frequently say that the Gothic style is a great achievement in art and engineering in the West, but its true beauty resides in how it can bring together many cultures.

European architects were able to achieve their own artistic and spiritual goals by using the pointed arch, a technology that was invented and improved in the Islamic world. The Gothic cathedral is not just a building in Europe; it is a world-famous monument constructed on a base of shared knowledge and borrowed brilliance.

In 2025, contemporary architects are reevaluating these fundamental components—not alone for their aesthetic appeal, but for the intrinsic structural rationale and passive climate regulation of these medieval designs. The pointed arch is a striking reminder that the best architectural ideas frequently go beyond time and place, bringing together people from many cultures in one beautiful, soaring vision.

References and Further Reading

Gothic Style: What Ideas Transformed Architecture?

For more content like this CLICK HERE!!