A Radical Beginning: Where Brutalism Came From

When people hear the word “Brutalism,” they frequently think of big, heavy concrete buildings that look more like fortresses than places for people to live. This architectural style came about in the middle of the 20th century as a response to the demand for simple, honest, and cheap building after World War II. It comes from the French word “béton brut,” which means “raw concrete.” It was a rejection of unnecessary decoration and a strong statement that everyone should be able to see what a building is for and what it’s made of.

Brutalism was most well-known for its use in public buildings in Europe and North America after World War II, but people often had strong opinions about it. Critics said it was too chilly, too harsh, and often too big to be welcoming. But in Brazil, a group of imaginative architects took this rough language of concrete and turned it into something quite different. They didn’t just copy the style; they gave it a life of its own.

The Brazilian Twist: A Conversation with Nature and People

Brazilian Brutalism, sometimes known as the “Paulista School” because it started in São Paulo, was more about poetry than strictness. Architects like João Vilanova Artigas, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and Lina Bo Bardi did not see exposed concrete as a cold, harsh material. Instead, they saw it as a way to interact with people and the environment. Their way of doing things was really different. Instead of making buildings that were closed off and defensive, they made buildings that were open, breathable, and closely connected to the land around them.

This desire to make people feel more human came from Brazil’s distinct environment and culture. The tropical sun, rich plants, and lively social life called for a new form of building. These architects employed concrete to frame the landscape, make huge open areas for people to gather, and make the distinction between inside and outside less clear. They showed that a material that seems harsh can be used to make rooms that are really pleasant, comfortable, and democratic.

Museu Brasileiro da Escultura e Ecologia, São Paulo, Brazil

The People Who Made Concrete Poetry

The Architect of Empathy: Lina Bo Bardi

The Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi may be the best example of how Brutalism can be made more human. Her work, which is a beautiful blend of modernity, popular culture, and social awareness, shows that architecture can bring people together. The Sesc Pompeia cultural centre in São Paulo is a great example of her work. Bo Bardi’s design kept the raw, industrial look of the old structures, which used to be a drum factory. It connected them to two new towers made of exposed concrete.

The Sesc Pompeia is not a monument to concrete; it is a busy public space. Bo Bardi’s design is based on its social function. It has broad, open spaces, walkways that enable people to mingle, and a strong respect for the building’s heritage. The iconic concrete sports towers, with their expressive apertures, look more like a fun, modern take on a mediaeval fortification than like brutalist blocks. It is a place where the “brute” material makes for a deep, personal experience.

Lina Bo Bardi Source: casacor.abril.com.br

Sesc Pompéia by Lina Bo Bardi Image via Wikipedia

Paulo Mendes da Rocha: The King of Simple Monuments

Paulo Mendes da Rocha won the Pritzker Prize for his work, which is known for its simple beauty and deep love for the nature. He thought of architecture as a way to make a second nature, a man-made landscape that fits in with the natural world. He designed the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture (MuBE) in São Paulo, which uses huge, raised concrete slabs to make the building feel light and blend in with the surrounding world.

Mendes da Rocha’s residential projects, including his own home, also demonstrate this way of thinking. He used exposed concrete to make peaceful places that were open to the tropical weather. He used big windows and courtyards to let nature in. The rough roughness of the concrete, which was often left over from the wooden moulds, became a warm and tactile aspect instead of a cold, hard surface.

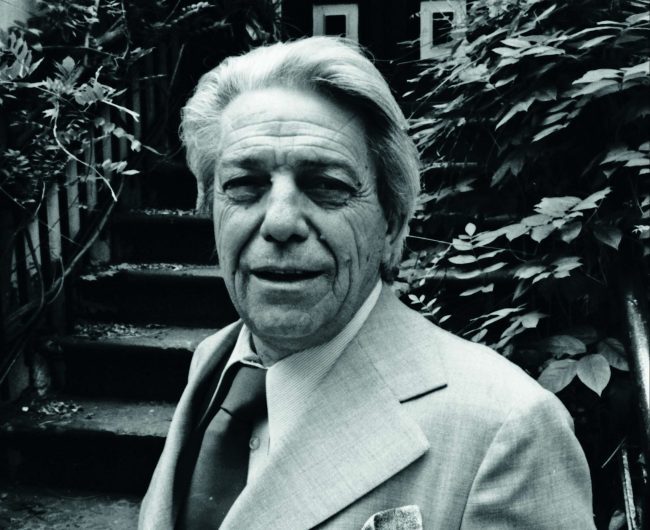

Paulo Mendes da Rocha (Ricardo D’Angelo/Veja SP

House in Butantã by Paulo Mendes da Rocha and João de Gennaro Image courtesy of The Modern House

The Social Architect João Vilanova Artigas

Vilanova Artigas was an important member of the Paulista School. He pushed for architecture that was socially responsible and helped the public. He thought that the strength of exposed concrete could be harnessed to make spaces that are democratic, open to everyone, and grand. The University of São Paulo’s Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU-USP), which he co-designed, is a great illustration of this idea.

The building is basically one huge covered plaza with a huge empty space in the middle and ramps that connect to each other in a way that goes against standard hierarchical patterns. The main level has no doors or closed-off hallways, which makes it a free-flowing, democratic space where everyone is equal. The concrete here isn’t scary; it’s powerful and a strong base for learning and working together.

João Batista Vilanova Artigas, one of the country’s greatest architects: ten-year exile in Uruguay (Judith Patarra/Veja SP)

Ginásio do Clube Atlético Paulistano by Paulo Mendes da Rocha and João De Gennaro, Image via Wikipedia

The Ideology Behind the Concrete: More Than Just Looks

The Brazilian Brutalist movement was not just a style decision; it was also a political statement. It came about amid a time of major changes in Brazil’s politics and society. Architects from the Paulista School thought that exposed concrete was a sign of development, honesty, and a dedication to constructing a new, contemporary country. Because the material was easy to find and not too expensive, they could make huge works that were both beautiful and useful.

This dedication to social usefulness is what really sets Brazilian Brutalism apart. Many of the structures were public places like universities, cultural centres, and museums that were meant to help people. They were robust, long-lasting, and honest about how they were made, which shows a desire for a fair and open society. The architects’ skilful use of light, space, and texture, along with this sense of purpose, turned what could have been a frigid style into one that was very warm and emotional.

Unité d’Habitation by Le Corbusier Image © metalocus.es

FAQs About Brazilian Brutalism

Q1: What is the biggest difference between Brazilian and European Brutalism?

The main distinction is how they think about the human experience. European Brutalism, especially in its public housing, was generally seen as cold and unwelcoming. On the other hand, Brazilian Brutalism used bare concrete to make open, permeable, and welcoming environments. Brazilian architects used natural elements, utilised expansive openings for air and illumination, and concentrated on fostering democratic, communal spaces.

Q2: Why did architects decide to use concrete as their main material?

We chose concrete because it is strong, cheap, and can be used in many ways. It was a good way to create rapidly and on a large scale. Brazilian architects, on the other hand, realised its expressive potential and used its rough, textured surface to show strength and honesty.

Q3: Will these constructions last?

This is a hard question to answer. Making concrete has a big impact on the environment, but these Brutalist buildings were generally intended to survive for centuries, which means that fewer new buildings need to be created. They were also made to work well in the tropics by employing natural ventilation and shade to cut down on the need for air conditioning, which made them very energy-efficient.

Q4: Where can I find well-known instances of Brazilian Brutalism?

São Paulo is like an open-air museum of the style. Some important buildings are Lina Bo Bardi’s Sesc Pompeia and Casa de Vidro, Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s Brazilian Museum of Sculpture (MuBE), and João Vilanova Artigas’s FAU-USP building.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Strength and Kindness

Brazilian Brutalism has a strong history. It makes us question what we thought we knew about buildings and materials. The works of Bo Bardi, Mendes da Rocha, and Artigas are not “brutal” at all; they are great instances of architectural humanism. They remind us that the real value of a structure is not its surface, but how well it connects with people, how well it celebrates the landscape, and how well it makes places that are both strong and delicate, monumental and very personal. Concrete wasn’t just raw in their hands; it was alive.

References

An Overview of Brutalism in Architecture

Brutalist Architecture in Brazil: Concrete Meets Nature – Artekura

For more content like this CLICK HERE!!