Introduction: The Lessons of Medieval Innovation That’s Sustainable

When we imagine a modern, sustainable skyscraper, we see glass, steel, and cutting-edge solar panels. But what if the plans for the most efficient tower of the 21st century were drawn up eight hundred years ago in the high stone naves of Europe’s great Gothic cathedrals?

Gothic architecture, which started in the 12th century, changed the way buildings were built. During the Middle Ages, architects had a really hard job: they had to figure out how to build buildings that were very tall using only stone, mortar, and human creativity, and they had to make sure they were full of light. The pointed arch, the ribbed vault, and the flying buttress were not merely pretty choices; they were brilliant examples of how to design with little material and be honest about how the structure worked.

As architects work to build homes that use no energy, they are looking past mid-century modernism and back to the smart engineering of the Gothic period. We call this mix of old-fashioned knowledge and new technology “Gothic Green.” It is a strong idea that the strongest, lightest, and most honest structure about how its forces are managed is the one that lasts the longest.

Experiments on the construction of the vaults in Notre-Dame: prototype in scale 1:3 (11/2020). Source: tandfonline.com

The Master Key: Ribbed Vaults and Efficient Use of Materials

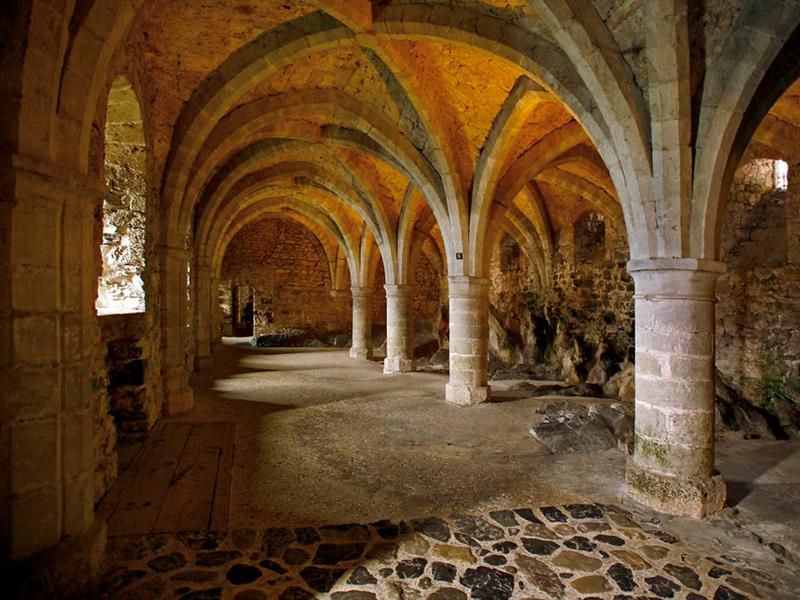

The ribbed vault is what makes the Gothic interior stand out. It’s a spectacular ceiling made up of stone arches that cross each other to form a skeleton. This was probably the most important new idea that let the Gothic design get rid of the massive, hefty walls of the Romanesque period.

Structure as a way to save money

The huge barrel vaults in a typical Romanesque ceiling needed walls that were several meters thick to hold the weight. The Gothic master builders figured out that they could instead focus the load. They directed all the weight to certain points—the columns and buttresses—by building a skeleton of load-bearing stone ribs. Then, the spaces between the ribs could be filled with thinner, lighter stone panels, or in the case of modern constructions, with lightweight or recycled materials.

This idea is now at the heart of a major trend in green building: using less material means less carbon is stored in it.

The Modern Application: Architects today use the ribbed vault technique to make concrete floor plates and mass-timber ceilings that work well. They can use up to 40% less concrete than a regular flat slab by adding geometric ribbing to a slab. This keeps the structure strong. This cuts down on the building’s carbon impact by a lot.

Ribbed Vaults Source: architecturecourses.org

The Flying Buttress Reimagined: An Outside Structure for Open Plans

The flying buttress is probably the most famous part of Gothic architecture. It is a grand arch that looks like it jumps from the ground to the side of the structure. It works as an external support that moves the heavy roof and high vaults’ huge outward thrust down to the earth.

By putting the structural support outside the main walls, medieval architects could make the interior walls very thin, which let in a lot of light and made the rooms feel quite tall. This is what structural efficiency is all about.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/buttress-168832073-57a9b86f3df78cf459fcec4c.jpg)

Saint Pierre in Chartres, France

Julian Elliott/robertharding/ Getty Images

From Support to Exoskeleton

current high-rise construction uses the same idea to make the most of space, light, and transparency, which are all important parts of current sustainable architecture.

Exterior Exoskeletons: Many of today’s skyscrapers have an exterior truss system or a new kind of structural exoskeleton. The Shard in London is an example of a Neo-Gothic building that is also Gothic in function. The construction is transferred to the outside, thus the inside is fully column-free and may be changed at any time.

Energy and Daylight: This outside construction lets the facade be practically all glass, which lets in the greatest light. Natural light coming in through windows cuts down on the demand for artificial light, which is one of the biggest ways a structure uses energy. So, the buttress principle is a straightforward way to cut utility bills and make people feel better.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/1626px-Flying_buttresses_of_Notre-Dame_de_Strasbourg-31d8dcc2ca5144b3943657d43a3e6a53.jpg)

Matthias Zirngibl from Germany/Getty Images

The Architecture of Light: Verticality and Passive Design

For the Gothic builder, light was a sign of the divine. For the sustainable architect, light is useful since it stands for free energy. Both tried to make the most of it by making it as tall as possible and adding big, complicated windows.

Getting Energy from the Sun

Gothic cathedrals employed their height and huge stained-glass windows to catch, filter, and spread light all day. This was a type of passive lighting design that was unlike anything else at the time.

Ventilation and Stack Effect: The Gothic nave’s great height and fullness also helped with natural ventilation. The “stack effect” idea, which says that warm air rises and is vented at the top, pulling in cooler air at the bottom, was employed to keep the building cool in the summer.

The “Gothic Green” idea tells current designers to think of the whole building envelope as a way to control heat and light. The idea is always to use the environment, not power, to be comfortable. For example, the high central atrium looks like a church nave, and the deep window reveals that block the sun during the hottest parts of the day.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-buttress-notre-dame-603331465-5b844a80c9e77c0025b01a06.jpg)

French Gothic Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

John Elk III/Getty Images

Conclusion: Structural honesty is the way to go for green building in the future

The “Gothic Green” movement teaches us that efficiency is not a new idea; it is a philosophy that has always been true. The best thing about the medieval master builders was that they made things beautiful by being honest about how they were built. They didn’t try to hide their load-bearing mechanism; they showed it out.

Architects are now accepting this honesty as we work toward a carbon-neutral future. We are not only making taller buildings, but also smarter ones by using the ribbed vault’s skeleton-frame efficiency, the flying buttress’s external support logic, and the high nave’s passive daylighting.

The skyscraper of the future, which will be built in 2025 and beyond, is not only a technical marvel, but it is also a structural descendant of the cathedral. This shows that the secrets to our most creative future are often found in our most creative past.

Reference

Understanding Rib Vaults: The Backbone of Gothic Architectural Design | ArchitectureCourses.org

For more content like this CLICK HERE!!