Gothic cathedrals, such as Notre-Dame, Chartres, and Reims, are engineering wonders that rise stubbornly against the sky and are likely to be seen if you stroll through any historic European city. Few people are aware, however, that the flying buttress—a crucial component of these structures’ success—lies just outside of their walls rather than inside. Often disregarded, this architectural breakthrough resolved a significant structural issue, allowing Middle Ages builders to create expansive, light-filled rooms with previously unheard-of verticality and beauty.

Lateral Thrust: The Architectural Issue

The weight of the roof and vaults created a tremendous lateral thrust, which was the main obstacle in the construction of large stone cathedrals with vaulted ceilings. The walls were forced outward by these forces, posing a collapse risk. In order to deal with this pressure, early Romanesque buildings built incredibly heavy and thick walls, which reduced the amount of light and space inside.

Something had to change as architects envisioned bigger naves and taller vaults. Such aspirations could not be supported by walls alone without becoming excessively large, which would make interiors gloomy, fortress-like, and inhospitable. It has to be a structurally and geographically liberated solution.

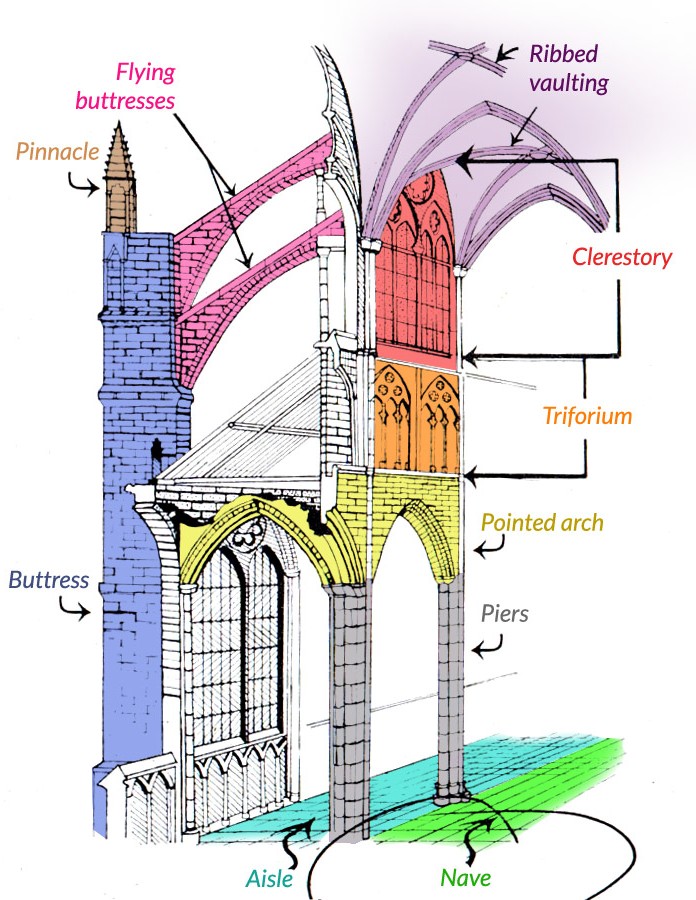

Interior (and some exterior) elements. Image: passport2design.com Original source: nvcc.edu

The Flying Buttress’s Inception

The solution was the flying buttress, an apparently straightforward but ground-breaking idea. This external support system used arching arms, or “flyers,” to carry the roof’s lateral push outside and downward to exterior piers rather than depending on thick walls. This made it possible for the inside walls to be taller, thinner, and punctuated with enormous stained-glass windows that let in heavenly light.

The flying buttress became a distinctive characteristic of Gothic architecture in the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly in France, even though similar concepts were present in earlier Byzantine and Romanesque construction. Saint-Denis in Paris, which was restored in the 1140s under Abbot Suger’s leadership, is among the oldest and most significant examples.

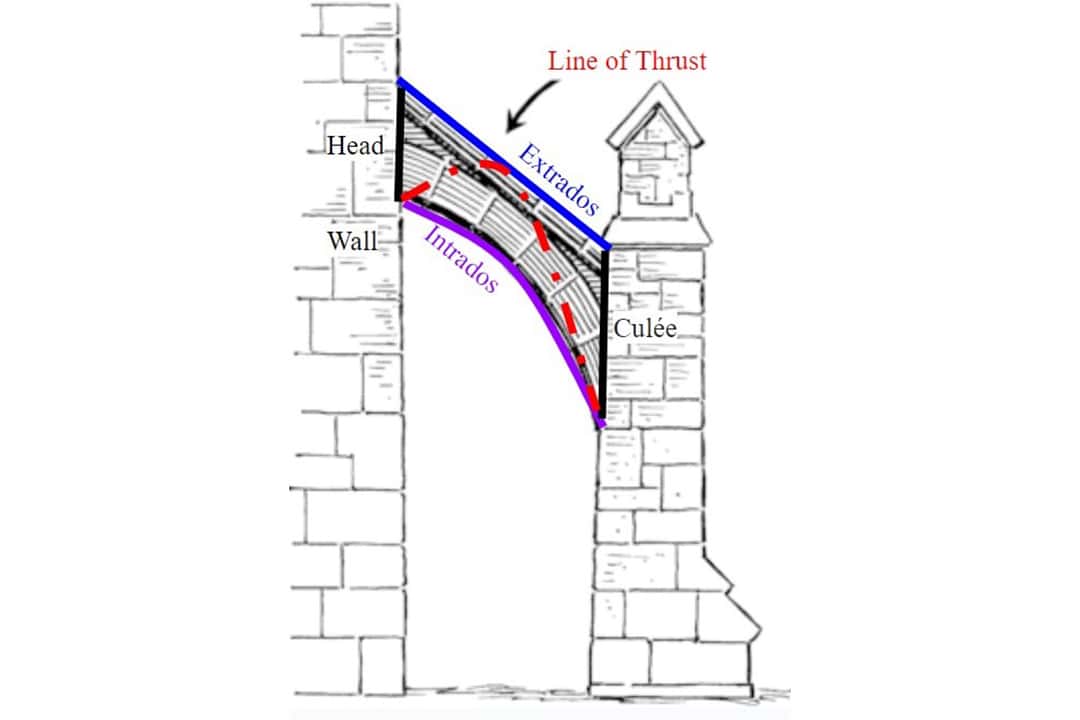

The components of a flying buttress. JEANINE VARNEY/THE VARSITY

Form Meets Function: Its operation

Typically, a flying buttress includes:

- An arched half-arch, or flyer, is a structure that radiates force from the upper wall.

- The force is anchored into the ground by a vertical pier or buttress.

- In order to offset uplift and wind force, a pinnacle—which is frequently decorative—adds vertical weight.

This arrangement reroutes force in a stable and aesthetically pleasing way by forming a triangle load path. In order to gracefully handle even heavier weights, Gothic builders improved the system throughout time by adding stacked piers, many levels of flyers, and adorned pinnacles.

Flying buttresses of Beauvais Cathedral: (a) Bending moments, (b) Normal forces, (c) Curve of pressure and actions against the structur.

Impact on Aesthetics and Symbols

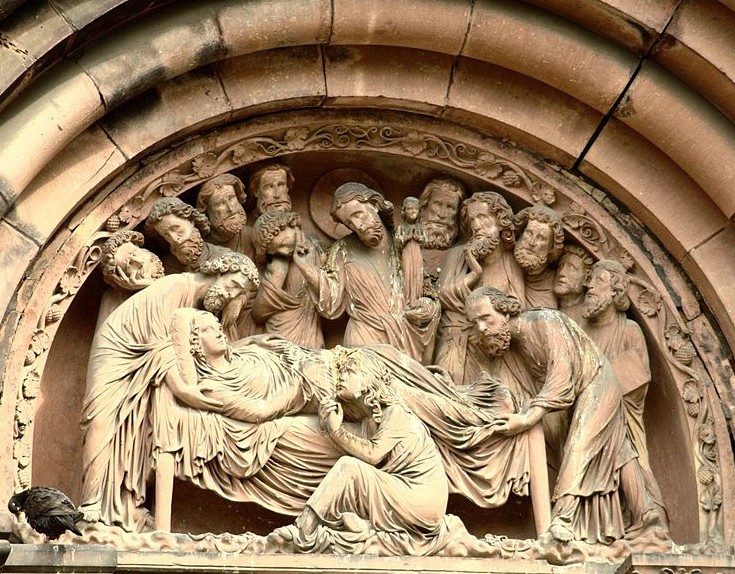

The flying buttress changed the way mediaeval people viewed sacred building in addition to being a structural marvel. Large stained-glass windows, such as the well-known rose windows at Chartres and Notre Dame, could be added by builders thanks to thinner walls. In addition to being aesthetically pleasing, these windows transformed cathedrals into “sermons in stone” by using light and colour to tell biblical stories to largely illiterate congregations.

On the outside, the Gothic silhouette incorporated the rhythm of flying buttresses. While the sculptural elements—gargoyles, crockets, and finials—added layers of narrative, utility (drainage), and flair, their repeating arching forms gave cathedrals a skeletal elegance.

The Lady and the Unicorn, tapestry, wool, metallic threads, silk; c. 1484-1500. App. 377 x 466 cm each. PD US http://www.tchevalier.com/unicorn/tapestries/taste.html

Pieces of the Flying Buttress Masterwork

Flying buttresses are responsible for the durability and beauty of some famous Gothic cathedrals:

- One of the earliest significant applications of the flying buttress in its visible form was at Notre-Dame de Paris (1163–1345). During construction, its tiered buttresses were modified to handle the increasing structural loads brought on by wider aisles and taller vaults.

- The Chartres Cathedral (1194–1250) boasts one of the tallest nave vaults and the best stained-glass programs in Gothic Europe because to its exquisitely crafted buttresses, which were essential from the beginning.

- The Reims Cathedral features ever more intricate buttress systems that minimise material bulk and maintain strength while including statuary, ornate tracery, and pinnacles.

- The soaring aspirations of the Beauvais Cathedral, which partially collapsed because to an over-reliance on fragile fliers and a lack of redundancy, serve as a warning about the dangers of pushing buttress engineering too far.

Chartres Cathedral, door jamb statues, west façade, 12th c. (1130-1160) By Giulia_ on Flickr. Creative commons

The tympanum of the South portal of Notre-Dame de Strasbourg , ca 1230, The Dormition of Virgin Mary, sandstone. CC BY-SA 2.0 Frédéric Chateaux

A Legacy of Structure

Even though flying buttresses were eventually rendered physically obsolete by materials like steel and reinforced concrete, their influence lives on. In cathedrals and public structures, architects from the 19th-century Gothic Revival, such as Viollet-le-Duc, reinstated and even emphasised flying buttresses. Their elegance can still be seen in exoskeletal structures and expressive bracing in contemporary designs.

Today’s architects see flying buttresses as early examples of form reflecting function, which is a fundamental principle of modernist and high-tech architecture, rather than only as supports.

Flying Buttresses in Popular Culture

The flying buttress frequently appears in popular media linked to Gothic horror, fantasy, or romance because of its unique profile. Flying buttresses are used to frame mystery, grandeur, and mediaeval mysticism in anything from video games like Assassin’s Creed to Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.”

Image credits: kobo.com

Conclusion: An Underappreciated Hero Deserving of Honour

These Gothic wonders were made possible by the flying buttress, even if stained glass, spires, and vaults garner more attention. It altered the course of architectural history by elegantly and efficiently resolving a challenging engineering problem. It made it possible for heavenly light to enter, freed builders from the constraints of high walls, and produced buildings that continue to amaze us to this day.

The flying buttress is, in fact, a representation of inventiveness as well as a practical feature. A reminder that sometimes the things that are holding us up from the outside are the ones that can bring about the most profound changes.

For more blogs like this CLICK HERE!

Reference

The Flying Buttress: Heroes of Gothic Cathedral Construction

Flying Buttresses: How They Changed Architecture | ArchitectureCourses.org